- Like I said, I’ll post this, it’s very long, but hopefully some people who read it will get some interesting stuff out of it. I dunno, just wanted to post an essay for a long time. NOTE: This is a 4 Star movie.

The Desire for Magic

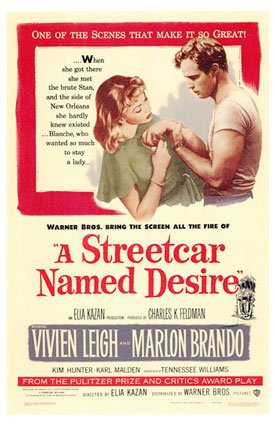

“I don’t want realism. I want magic!†This line is bawled when, in the play A Streetcar Named Desire, the delusional character Blanche DuBois confesses to her lies, to her insanity, and furthermore to her desire to feel life through dramatic intensities. The motion picture, based on playwright Tennessee Williams’s visionary masterpiece, pushed this statement even further with a stunning new set of cinematic visuals and camerawork in 1951 under the direction of Elia Kazan. To this degree, the movie greater communicates to the audience the madness and beauty of Blanche in her most desperate and seductive moments than the original play in its derived presentation.

“I don’t want realism. I want magic!†This line is bawled when, in the play A Streetcar Named Desire, the delusional character Blanche DuBois confesses to her lies, to her insanity, and furthermore to her desire to feel life through dramatic intensities. The motion picture, based on playwright Tennessee Williams’s visionary masterpiece, pushed this statement even further with a stunning new set of cinematic visuals and camerawork in 1951 under the direction of Elia Kazan. To this degree, the movie greater communicates to the audience the madness and beauty of Blanche in her most desperate and seductive moments than the original play in its derived presentation.

Scene six of the play places Blanche on a date with her new beau, Mitch. The coming together and falling apart of these two characters can be seen as one of the major tragedies of the play. Towards the conclusion of this scene it is shown that Blanche does in fact need Mitch, and in a way- though far less severely- Mitch needs her. The film helps establish to a greater degree than the play that Blanche is constantly spinning a web around Mitch through deceitful fantasies and her own unnoticed inner delusions.

There are many differences between the text of the play and the text of the screenplay inevitably seen in the film. One blatant change in adaptation comes in the setting. In the original text, Tennessee Williams wrote Blanche’s victory over Mitch’s heart to take place inside the empty Kowalski’s house while the lord and lady of the residence are out on their own late night prowls. Instead of showing the remaining struggles of Mitch’s affections after a frustrating date with Blanche, it takes a liberal step backwards into an actual date- a move which actually gives the audience a peak into the very brief and shallow social interactions that guise the true troubles of this doomed relationship. Underlying changes in dialogue, such as Blanche citing her need to stay formal as a reaction to being in public, help show that she tenaciously wishes to keep her façade prevalent even when away from her sister Stella.

There is also one drastic change in the script that for a moment changes Blanche’s character completely from the text in a way to offer more sympathy towards her. Both the play and the film have Mitch pose the personal question in reference to

character completely from the text in a way to offer more sympathy towards her. Both the play and the film have Mitch pose the personal question in reference to

Taking this one step further, the monologue Blanche uses to describe her relationship with her late husband Allan is cut immensely. This primarily could be a result of censorship at the time that would have been against any mentioning of homosexuality in a film; however this did not phase the success of the film’s expression of Blanche’s plight. Removing her direct description of events such as “Then I found out… By coming suddenly into a room that I thought was empty- which wasn’t empty but had two people in it… the boy I had married and an older man who had been his friend for years…†(95), helps to add more of a cloud around her motives as to her distress. In the film, all her reasons for loathing Allan are spoken only after one direct phrase: “I killed him.†This takes Blanche’s character to a whole new dimension, putting an exclamation point on her guilty conscience- appealing to the protectiveness demonstrate by Mitch throughout both mediums of the story. This one substituted line of dialogue places her into a new category from damsel of outside distresses, to damsel of her own distresses. She has become even more sympathetic because of her own self-hatred, and the blame that can be put on her for Allan’s death is harder for the viewer to place. By taking away words, her character’s dream and vision has become more complete.

Dame Blanche’s key goal is to create an illusionary world of her own, filled with magic of both joy and despair. In order to survive in this world she needs to draw in others- her next victim being the hapless, hopeless Mitch. The direction crafted with the mis-en-scene and camera work of this scene elevates her ability to draw Mitch into her surreal with her own form of smoke and mirrors. The first obvious gesture towards the dream world is Blanche’s leading of Mitch out of the swing club and into the quiet, calm and lonely dock area, where the two are isolated only to Blanche’s dramatic whims. The scene begins with Blanche and Mitch sitting outside the club, with dirty blinds and a curtain that leads out towards the docks- always placed behind Blanche as if emphasizing that she is about to lead Mitch into a dramatic performance. As the couple moves towards the docks further, the people inside the club can be vaguely seen through a window, until the camera shifts and the whole world disappears. One last couple drifts by and as Blanche recalls he